Get the Facts: PFAS in food packaging

To make food packaging resistant to oil and liquid, some companies add chemicals called PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances).

PFAS are highly persistent, mobile, and toxic chemicals. Their manufacture and use in food packaging and other products has resulted in widespread contamination of drinking water. While companies like DuPont, 3M, and Daikin have profited from producing these chemicals, communities around the U.S. are struggling to remove them from their drinking water sources at great expense. The extent of the toxic legacy we face from the use of PFAS is still unknown—contamination is uncovered in new communities almost weekly.

Some PFAS are so persistent that they don’t degrade in the environment—so levels will only get higher over time if their use continues.

The solutions to this problem exist—we just need leaders to implement them. Alternatives to packaging with PFAS are readily available and competitively priced. And because of growing concern, major retailers from Whole Foods to McDonald’s have committed to phasing PFAS out of their packaging. Six states have already passed bans on PFAS in food packaging that will take effect soon. As retailers, municipalities, and states take the lead, momentum for Congressional action grows.

How are Americans exposed to PFAS through food packaging?

The chemical industry makes PFAS for use in paper used to serve, display, or package food, to stain-proof furniture, carpets, and clothing, in firefighting foam to fight oil-based fires, and in many industrial uses. People are exposed to PFAS through multiple routes, including food, dust, air, and water.

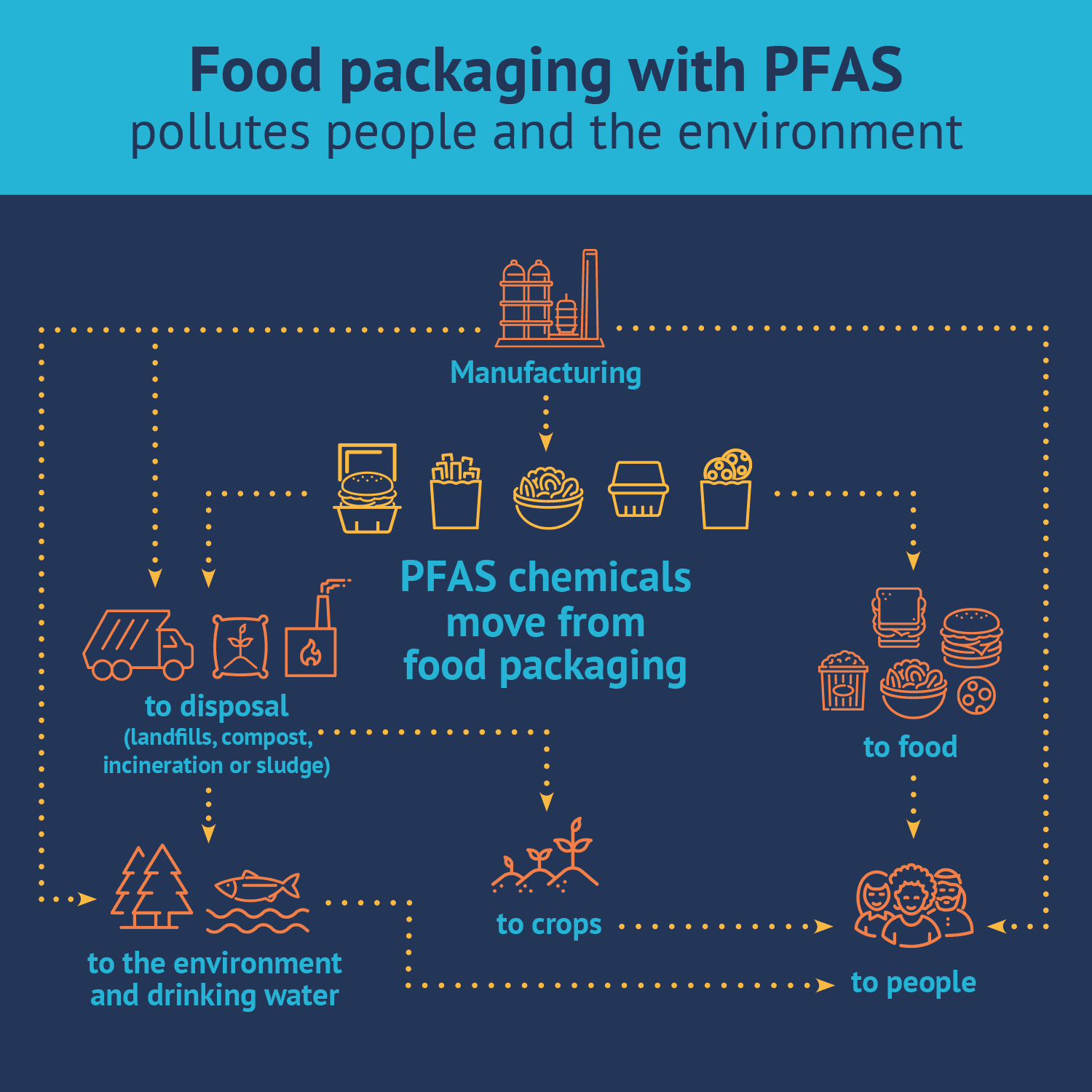

Testing has found these chemicals in various paper takeout packaging—from burger wrappers to salad bowls—as well as microwave popcorn bags and other items such as paper bags for baked goods. PFAS can contaminate the food inside the packaging—but before that, they can pollute the communities where the chemicals and packaging are made. And after an item holds food briefly, it can pollute the communities where the trash is composted, dumped, or burned.

This creates a long-term problem because as the packaging breaks down, it releases its PFAS into the environment. Then the chemicals can make their way back to people through drinking water, food, and air. Food crops and gardens can become contaminated with PFAS-containing compost, as shown from research demonstrating plants, such as lettuce and tomatoes, take up PFAS from soil.

Why should we be concerned?

PFAS are extremely persistent in the environment and some of them build up in people and animals. Once they are in our bodies, they stick around—with half-lives in people of up to eight years. Nearly every U.S. resident has PFAS in his or her body, with biomonitoring studies finding PFAS in blood, breast milk, umbilical cord blood, amniotic fluid, placenta, and other tissues.

A peer-reviewed study published in May of 2021 found PFAS in 100% of breast milk samples tested. The study also found detections of these chemicals in breast milk to be on the rise globally and doubling every four years.

In March of 2020, a consortium of scientists published a new scientific statement sounding the alarm about toxic chemicals such as PFAS in food packaging.

Exposure to these compounds has been linked to a number of health concerns, including:

- cancer

- hormone disruption

- liver and kidney toxicity

- harm to the immune system, including decreased response to vaccines

- reproductive and developmental toxicity

How did we get here?

In the early 2000s, the dangers of the first PFAS chemicals were exposed by lawyer Rob Bilott and his clients around the DuPont plant in West Virginia (the story dramatized in the film Dark Waters and recounted in the documentary The Devil We Know). Reports suggest the makers of these chemicals, 3M and DuPont (now Chemours), had enough information decades ago to know that certain PFAS were harmful. Yet they continued to make them and put them on the market to pollute people, wildlife, and communities.

The PFAS crisis demonstrates the failure of the existing systems that govern chemicals. A major shift in the systems to ensure that only the safest chemicals and materials are allowed into commerce is critically necessary.

Stopping the chemical “whack-a-mole” game

Some PFAS chemicals have been phased out of consumer products as data about health hazards have been identified chemical by chemical. But the companies replaced them with very similar chemicals in the PFAS class, which now has thousands of compounds. This is a classic case of regrettable substitution or chemical “whack-a-mole.”

As these current-use PFAS are more mobile than the old-generation PFAS, they can migrate more readily into food. Studies on the current-use PFAS have found health effects similar to those caused by the older compounds that have largely been phased out.

Research recently published by scientists at the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) shows the PFAS in current use are bioaccumulative and more toxic than FDA previously acknowledged. To avoid regrettable substitutes, the entire class must be phased out and safer alternatives must be used.

What about alternatives?

In a recent study, 67% of tested packaging from major fast-food chains was PFAS-free, demonstrating that alternatives are widely available and competitively priced.

We have assembled a list of alternatives that restaurants can purchase as well as guides for grocery stores and quick-service restaurants that want to remove all PFAS from their packaging.

Reusable food serviceware is also widely available and preferable to single-use items.

States, municipalities, and retailers stepping up to ban PFAS in food packaging

In the absence of federal leadership to protect health and the environment, states and retailers are stepping up. Washington state passed the first state measure to restrict PFAS in paper food packaging in 2018, which helped start a cascade of companies switching to PFAS-free.

A number of U.S. fast-food and fast-casual restaurants, including Panera Bread, Chipotle, McDonald’s, and Wendy’s, have publicly committed to ban PFAS from consumer-facing packaging. In addition, several grocery companies have announced steps to reduce PFAS in food packaging. See the full list of commitments here.

In addition to Washington, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, New York, and Vermont have passed laws banning PFAS in food packaging that will go into effect soon. Bans in San Francisco and Berkeley have already gone into effect. In all these cases, the bans cover the entire class of PFAS. Momentum continues to grow as more states consider bans.

Now, Congress must act

Responding to growing public demand, Congress will act on legislation to end the use of PFAS in food containers. Representative Debbie Dingell (D-MI) recently re-introduced the Keep Food Containers Safe from PFAS Act (H.R. 6026). Senator Maggie Hassan (NH) introduced a Senate version of the bill (S.3169), which has been co-sponsored by Senator Lisa Murkowski. This legislation is a critical step to ending the PFAS pollution crisis plaguing communities across the country.