Seven years ago my father died from pulmonary fibrosis. His lungs had developed so much scar tissue, that over the course of about a year he went from a healthy, vibrant father and grandfather to essentially being suffocated by his own failed lungs. He was 68, and just two years into the retirement he had dreamt of for decades.

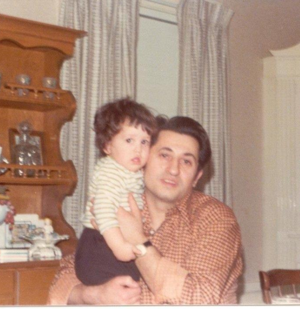

My father, Letizio, spent just about twenty years working in a factory in Hartford, Connecticut that produced ceramic parts used by electrical companies. It was a hard, monotonous job, but he was glad to have it. He had grown up poor in post-World War II Italy, and had about a sixth grade education.

The pay was decent, and overtime was plentiful, and he’d eagerly snap it up to bring home extra money to save for his kids’ education and his retirement. He was also able to improve our lives and accomplish the American dream: two cars in the garage of a nice suburban house.

Once as a child, I visited the factory floor, and saw the machine my father stood over, stamping out parts that helped make America hum with electricity. It was hot in there, and the place was filled with dust. Decades later, we would learn that dust was a toxin called kaolin, a fine naturally occurring particle used to make plastics and ceramics. He

breathed it in every day, lots of it, for twenty years.

The specialists my father saw when he became ill said they’d seen many cases from people who worked at the same factory, known as the Hartford Fiance Company. The kaolin, much like asbestos, got trapped the lungs of these workers. Years later, it would lead to lung disease like the pulmonary fibrosis that claimed my father. His last words came to us in a midnight call from the hospital. His lungs had failed and the doctors were going to put him on morphine and a respirator. He would not be conscious ever again. His said into the phone line. “I love my wife, I love my family.”

There was no justice or compensation for my father. Like many factories in the northeast, Hartford Fiance Company was long shuttered.

Workplace exposure to toxic chemicals far too common

I wish we could say we’ve learned the lessons of the industrial era, but we have not. Last March, the New York Times told one heartbreaking story of a woman and her coworkers employed at a factory assembling furniture. The fumes from the glue formed a yellowish fog inside the plant, and breathing them in led doctors to conclude that it ate away at the workers nerve endings, producing what workers there called, “dead foot.”

The Times goes on to say chronic ailments caused by toxic workplace air — black lung, stonecutter’s disease, asbestosis, grinder’s rot, pneumoconiosis — incapacitate more than 200,000 workers in the United States annually. More than 40,000 Americans die prematurely each year from exposure to toxic substances at work — 10 times as many as those who die from the refinery explosions, mine collapses and other accidents that grab most of the news media attention.

There’s substantial cost to the economy as well. About one-quarter trillion (with a T, yes) annually in lost productivity and medical costs.

Labor Unions Fighting for Worker Health & Safety

About four million people in the United States go to work as janitors, cleaners, housekeepers, landscaping and groundskeeping workers, pesticide handlers and other maintenance occupations. Unlike my father’s job, these often don’t pay decently, meaning these workers get even more risk and less reward than my dad did decades ago. Dangerous chemical exposures remain common according to Safer States analysis of worker data.

According to workers’ compensation data, six out of every 100 custodians have a lost-time injury every year due to chemical exposure. The majority of injuries involve eye irritation and burns, skin irritation and burns, or breathing chemical fumes. And these are just the short-term effects.

Janitors and other service workers often lack the means, skills and time to organize, but their unions speak for them and are working with environment and public health groups to clean up our workplaces. As unions lobby for better pay and benefits for their workers, they are also lobbying for healthier workplaces and safer chemicals.

“[Green cleaning] has become more of a priority at the bargaining table as everyone’s consciousness begins to rise about the importance of having a green work environment,” said a national Service Employees International Union

spokesperson a few years back.

Similarly, the Blue-Green Alliance, a partnership of labor and environmental health groups (and coalition partner), leads an initiative to get safer products into workplaces. Replacing safe products for hazardous ones, and using preventive methods to reduce workplace exposures. It makes me wonder, if my father’s factory had used safer alternatives and better safety equipment, might he still be with us today, enjoying a burger and hot dog at our Labor Day picnic?

As you might imagine, Labor Day is special to me. Our nation was built on hard work and sweat in the expectation that work would bring prosperity. That is certainly still possible in America, but we have a long way to go.